Infrastructure is now a critical growth story for the global economy. From data centres powering artificial intelligence (AI) to building the grids needed to support electric vehicles and the renewable energy transition. This article by Assistant Investment Manager, William Redmond, explains why robust infrastructure is essential for future economic growth and a good potential source of portfolio returns.

Infrastructure: The Invisible Backbone of a Changing World

1. The AI boom has a physical problem

If you only followed the headlines this year, there’s a danger in thinking the global economy was driven entirely by politics, interest rates and whatever the latest tariff dispute was. But beneath the noise, something extremely important is unfolding: the world is being rebuilt from the ground up. Infrastructure, long dismissed as the sensible but slightly dull corner of the investment universe, has become one of the most strategically important asset classes.

This isn’t the infrastructure of the past. It is the wiring and plumbing of the future economy: the grids needed to power AI data centres, the networks that support electrified transport, the airports and toll roads benefitting from demand due to a population of global travellers, and the renewable systems that must grow if the lights are to stay on. The macro outlook may be uncertain, but one thing is not – the world needs more infrastructure.

2. Data Centres: The new nerve endings of the global economy

It is easy to imagine the digital world as something floating “in the cloud”. In reality, “the cloud” is deeply physical. The cloud lives in vast, windowless industrial buildings filled with servers, cooling systems and fibre connections. These data centres have become the nerve endings of the global economy, consuming as much electricity as small towns, and acting as the processing hubs of our digital lives.

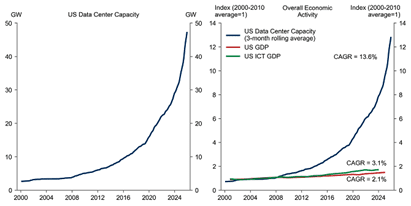

Training and running AI models requires enormous computing power, and that demand has turned data centres from niche assets into core infrastructure. It has also triggered one of the largest corporate investment cycles in history. Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet and Meta are now spending at a scale normally associated with national energy systems, not technology companies. In 2025, according to Statista, a global data and business intelligence platform, the four firms alone are expected to pour over $350 billion into capital expenditure, with the majority of that directed toward AI infrastructure and data centres. To put that in perspective, London’s Elizabeth line – one of Europe’s largest recent infrastructure projects – cost around £19 billion and took over a decade to build from groundbreaking to opening. We could rebuild the Elizabeth line 18 times with the amount of capital these businesses have deployed into AI development in 12 months.

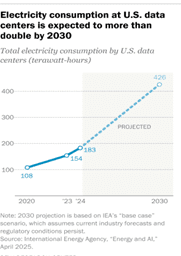

Global data centre electricity use has already hit 415 TWh, and is on track to more than double to around 945 TWh by 2030 – roughly equivalent to Japan’s entire electricity consumption per year. Every stream, transaction, diagnosis, logistics update and AI query passes through these buildings, consuming energy as it does. If the digital economy is the brain, data centres are the synapses, firing constantly.

Source: Aterio, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research & Pew Research Centre

3. The Power Grid: A circulatory system under strain

The power grid we rely on today was built for a different world, a world of predictable demand and fossil-fuel generation. The grid of the 20th century was never designed to support AI, electric vehicles, heat pumps, or thousands of data centres running 24/7. Running alongside the technological demand from AI, today the power grid is going through a transition from fossil fuel to more sustainable energy supply, whilst also facing a significant increase in demand from this new technological era, which has its own investment demands.

Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BloombergNEF) expects electricity demand from AI and data centres to hit the equivalent of roughly the entire consumption of India by 2035. The International Energy Agency (IEA) warns that electricity demand is rising faster than grid capacity, and that the world will need to double its transmission lines by 2040, which equates to over 80 million kilometres of new or upgraded lines. That’s enough transmission lines to wrap around the Earth 2,000 times.

Governments are scrambling to catch up. The US Inflation Reduction Act is pumping billions into grid upgrades, the EU plans to invest €584bn before 2030, and the UK is fast-tracking approvals that once took years. The National Energy System Operator has recently reformed the grid connection process to prioritise ‘shovel ready’ projects over the old first-come, first-served queue, aiming to clear gridlock, unlock billions of pounds of investment and significantly shorten connection timelines. But the scale of the challenge remains vast: global grid investment needs are expected to exceed $21 trillion by 2050, according to BloombergNEF.

Electrification and renewables: Rewiring the body of the economy

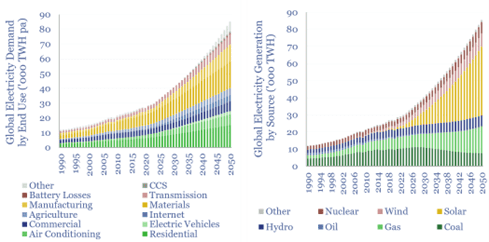

AI workloads, electric vehicles, heat pumps, and automated factories are significant consumers of energy; however, global energy supply systems are facing challenges in meeting this growing demand.

Renewables have become the answer not only because they are ‘green’, but because they are a scalable, cost-competitive source capable of meeting this acceleration. Clean energy investment now outpaces fossil fuels two to one, and the world is set to add 4,500–5,000 GW of new renewable capacity by 2030, more than double the last five years’ build-out.

Nuclear power is also re-entering the energy conversation as governments seek reliable, low-carbon baseload generation to support an increasingly electrified economy. While large-scale nuclear projects remain capital-intensive and slow to deliver, smaller modular reactors are being positioned as a more flexible, incremental alternative – though still early-stage and facing regulatory and execution headwinds.

But the bottleneck isn’t generation. It’s infrastructure. Transmission lines, battery storage, grid connections and flexible distribution networks are all far behind demand. The Energy Transitions Commission (ETC) estimate trillions of dollars in new power investment will be needed every year just to keep pace. For all the hype around AI, electrification is what actually makes it possible. The world is in a race to build enough infrastructure to power the economy it is creating.

Source: Thunder Said Energy

Source: Thunder Said Energy

4. Geopolitics: Strengthening the spine of national resilience

Infrastructure has become a tool of national power. Countries are no longer building simply to support growth, but to secure themselves in a world where technology, energy and supply chains are being contested. The rivalry between the US and China now runs through physical infrastructure. America is reshoring semiconductor production while China dominates solar, batteries and critical minerals. Both sides are accelerating investment in energy capacity and data networks because AI capability increasingly depends on who controls the chips, the electricity behind them, and the fibre routes that move their data.

Europe has undergone its own shift. The energy shock following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine forced resilience, driving a rapid build out of LNG terminals, offshore wind and cross border grid links. At the same time, big global pinch points remain – around 97% of international data travels through undersea cables at risk of disruption, most rare earth processing is concentrated in a single country, and major shipping routes like the Red Sea and Panama Canal can be disrupted by conflict.

Perhaps the greatest focus is the semiconductor arms race, making it the most strategically valuable infrastructure of all. Advanced chips are now treated as instruments of power, and the companies behind them sit at the centre of global geopolitics. Nvidia, now worth over $4 trillion, controls more than 80% of the market for AI training chips, while TSMC manufactures around 90% of the world’s most advanced semiconductors and produces the chips used by Nvidia, Apple and the US defence industry. This concentration of capability has formed alliances, from US-Japan-Netherlands cooperation on chipmaking to Europe’s emerging energy partnerships with North Africa and India’s rise as a supply chain hub, but it has created significant global tensions too.

The scale of capital now being deployed is not without risk. Spending vast amounts of money on new infrastructure comes with established risks. Big investment booms of the past, whether it was the railways, telecommunication systems, or the early internet, have tended have eventually deliver an over-supply, compressing returns and triggering price pressure when capacity is built faster than utilisation. This makes selectivity critical as not all assets, regions or operators will benefit equally from the build-out.

Infrastructure: Where resilience meets growth

Infrastructure has always been the dependable corner of portfolios – steady cashflows, inflation linkage, regulated returns. What’s changed is the world around it. The race to build enough power, connectivity and industrial capacity for an AI-driven economy is transforming infrastructure from a defensive asset into a growth engine. Every major theme shaping markets today – AI, electrification, reshoring, energy security, semiconductor rivalry – ultimately depends on physical systems that simply do not exist at the scale required.

That’s why we see infrastructure as one of the most interesting long-term stories in markets. Demand is rising across every level of the system. Governments and companies are being pushed into a multi-trillion-pound investment cycle that is not optional, it is necessary. We believe infrastructure assets provide exposure to the same structural forces driving technology markets, but through the real-world build-out that underpins them, in contrast to a set of highly valued equity stocks. Unlike many growth stories, this one is rooted in essential services the world cannot function without.

Infrastructure is no longer the ‘boring’ part of the economy – it is the backbone of the new one. It offers resilience when markets are volatile, and meaningful upside as the global race for power, capacity and technological independence accelerates. We believe it will remain a core contributor to long-term portfolio stability and growth.